Blau International No.3: REINVENTING THE DEAL

REINVENTING THE DEAL: After a year of revolt, restlessness, and ruin, Mira Dayal investigates how pioneering galleries in New York, Toronto, Los Angeles, and Monterrey can not only survive, but effect real change in their communities

By Mira Dayal

February 2021

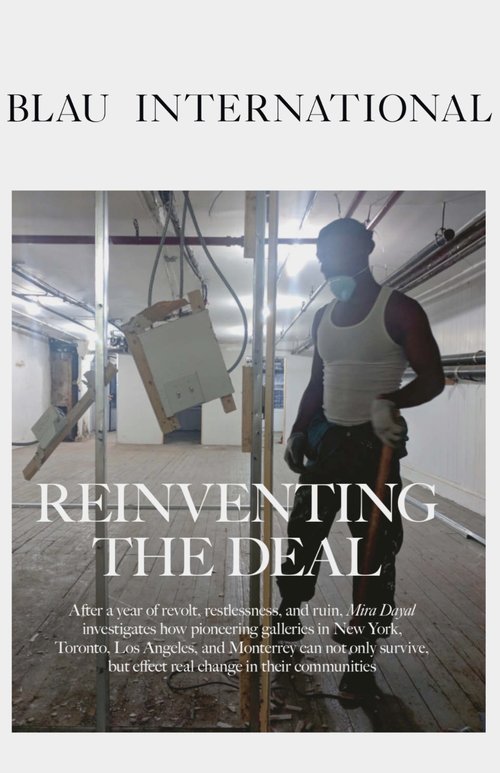

It feels like I’m on a raft, and there are multiple hands creating a current in the water; they’re ushering me through,” Onyedika Chuke tells me. “That’s what turned this space into a gallery.” The space, which the artist built out himself, is a two-room basement in New York’s Chinatown called Storage Projects.

I visited the inaugural exhibition in the fall, after a summer of sickness and protest had left the city feeling both sapped and sharpened. During the shutdown, most galleries settled for online exhibitions, but some responded more directly to the protests. The Housing gallery, for example, held a and, from the window of its new space on the Lower East Side, screened a series of artists’ videos on social justice, including Howardena Pindell’s iconic Free, White, and 21 (1980).

Now that spaces were open again, the Storage Projects show caught

my eye for its inclusion of two artists in particular, one established, the other fresh off her MFA: Leslie Hewitt, who presented an extension of her series that involved a print of a subtly altered green grid, and Jazmine Hayes, who screened a video that deftly intercut black-and-white and more recent videos of primarily Black women performers. Alongside these works were contributions by artists in their early 20s (Daniella Portillo) to their late 70s (Emory Douglas, who was minister of culture for the Black Panther Party—some of its archived newspapers were on view). What united the artists, Chuke emphasized, was that “they’ve all been a part of mutual aid modalities in their own communities.”

Working with socially engaged artists is important to Chuke, who has dedicated much of his career to education and community support: “It’s artists supporting other artists. We have a pool of artists that have skill sets they’re able to lend to other people who need those skill sets.” Other dimensions of the gallery, from its mandate to show at least 50 percent women artists to its planned mentor- ship program for young BIPOC artists and its additional program to nourish protestors, are reflective of a larger effort to restructure art galleries or, in some cases, scrap current models altogether.

The momentum has been driven by the social justice movement, but also by industry-specific forces such as Death to Museums (an“unconfer- ence” for museum workers to “incite radical thinking and actionable change”) and @cancelartgalleries (an Instagram account publicizing gallerists’ egregious behavior as well as the discrimination many artists and art workers face in commercial art spaces). Over the past few decades, larger galleries have swelled and swallowed smaller galleries, often amplifying existing inequities and wealth disparities. What can new art galleries offer in this context, and in what ways are young spaces actually pushing the model?

Like Chuke, the directors of Murmurs in Los Angeles—Allison Littrell, Morgan Elder, and Gabrielle Datau—have been inspired by mutual aid models. Their space is now almost 18 months old and moving toward nonprofit incorporation. According to the mission statement, it “strives to dismantle the racist capitalist paradigm that the conventional art world has evolved from.” Storage Projects employs similar language but positions decolonization as its . Chuke elaborated: “That ideal of decolonizing the system... Right now, it’s a sexy thing to say. But after six months to a year, we’ll see who’s holding true to it. That’s what got me to where I am now— challenging systems. I think you have to massage newness into a system.”

Murmurs resisted commercialization from the start; the space also contains a café and a store that help to compensate artists (Storage Projects has an etching press for a similar purpose). Yet, over the summer of protests, the directors felt that they could be doing much more: “That was a pivotal moment for us,” Littrell told me. Other institutions’ gestures often seemed performative—“a lot of black squares, a lot of reposting images. For me, it felt that art paled in comparison to what else was going on in the world. Essential workers are risking their lives every day, and no one really needs our gallery in a dire way.”

Having set down a new plan of action, Murmurs cook weekly meals for unhoused locals, invite mutual aid and social justice groups to use the space, host annual fundraisers for Black Lives Matter, offer editorial and design services, and allow Black artists to keep 100 percent of the proceeds from sales of their work. These concrete plans are complemented by less tangible goals, such as “organize more exhibitions and programs with BIPOC artists.” The latter is commonly voiced by many other galleries, but it often rests on a shifty interpretation of “more” or stops at the level of representation, without larger commitments to the financial, legal, individual, and community needs of BIPOC artists. “What we’re trying to do here is make a new model for an art space,” the directors explain.

These galleries’ efforts are in some ways specific to their locations. Chuke’s artist mentorship program will draw

on grassroots networks he developed from working with the city’s educa- tional and foster care systems. Murmurs is able to fund its exhibition program because it occupies a large multiuse space in a downtown industrial neighbor- hood. But other venues could surely adopt these actions, translating them to other locales and more traditional commercial spaces.

Peana sits somewhere between models, spanning a commercial gallery space, a nonprofit residency program, and occasional exhibitions elsewhere in the Americas. Ana Pérez Escoto opened the space in 2016 in her hometown of Monterrey, Mexico, roughly 900 kilo- meters north of Mexico City and home to the contemporary art museum MARCO. In our discussion about the gallery’s recent shifts, context was again important; in Mexico, rising femicides— 10 women are killed every day—led to widespread protests in 2019 and a national strike this March (tens of thousands of women withheld their labor). Escoto’s response at the gallery was relatively straightforward: show more female artists and queer artists, keep group shows gender-balanced, and support a gallery staff of at least 50 percent women.

But Peana is also focused on community education and engagement, and on US visibility for Mexican artists through art fairs, collaborations, and exchanges: “with the wall and Trump, and everything that was going on, I felt there was a need to reiterate how important the connection between these two countries was.” Escoto started the residency to enhance that relationship, inviting US artists to work with the local art scene, which she says has been reinfused with young artists from the city’s university, now boasting a Tadao Ando building. The gallerist initially found funding from the Rockefellers—a detail that art activists might find troubling, given the origins of the family’s fortune in the Standard Oil Company—but the gallerist hopes to find donors for the program within Mexico. The residency encourages social practice: artists create work or lead discussions with Monterrey artists throughout the city and its parks. An upcoming project will involve billboards responding to the feminist movement.

In Toronto, one new commercial gallery is Patel Brown, a joint venture of Devan Patel, who formerly ran his own gallery, and Gareth Brown- Jowett, previously a director at Division Gallery. Their first exhibition, , opened during the summer. The press release outlined the gallery’s mission, including a “commitment to continued learning, authentic community engagement, and to support[ing] growth through the respectful and expansive exchange of diverse viewpoints.”

In an ongoing series of essays, Brown and Patel also commission writing that responds to sociopolitical issues in the arts. In an essay from June, Devyani Saltzman suggests that “there is a world of allies out there, including those in leadership and governance, who are willing

to break down whiteness at the top.” Sharing her own experience as a mixed-race woman balancing advocacy and acceptability, she added that, without a power shift, “the dissonance continues, and BIPOC folks continue to carry the burden of progressive mandates misaligned with internal lived experience.”

The power shift Saltzman called for must also manifest in more structural ways, through ownership and economic security for Black and marginalized artists and art workers, something that Housing’s founder, KJ Freeman, highlighted in our conversation: “In July, we started a grant program. We gave $1,000 out to five Black radical women who were either artists, curators, or art-adjacent writers.” The initiative was part of a larger shift, parallel to the gallery’s move from Bed-Stuy to the Lower East Side,” into a hybrid between a commercial art space and a community center or a non-profit space, where we try to give as many resources to our community and our art community as possible.” The relocation was complicated; Freeman attributed the wider interest and more rapid sales partly to the space’s new “proximity to whiteness,” a marker of accomplishment in the art world. Galleries have a fraught relationship to whiteness more broadly. As the gallerist wrote in a Spike essay, the space “is white because it represents extraction, which is the basis of white supremacy.” This brings us back to the protests—for Black life, against white supremacy—and the urgency of overhauling the gallery system.

Freeman is trying to run a gallery that is not extractive. Housing was shaped against contemporary white art spaces (“What would a Black gallery in Montmartre be like in 1890?”). It has continually championed emerging Black artists while developing strate- gies to help them sustain their momentum, against the draining forces of market trends and speculation. “I want my artists to do well,” Freeman said. “I want them all to have the ability to pay their rent without freaking out. I want them to have health.”

Autonomy and sustainability are concerns for each space, especially those with more comprehensive and less traditional plans. The Murmurs directors mentioned the challenge of sustaining their many-pronged mutual aid efforts in addition to artists’ projects. Chuke noted that his detailed designs for mentorship, skill sharing, dialogue, shared meals, and empathetic support are ideally the building blocks of something like an art center that would own property—and he hopes other people will feel empowered to come through grassroots systems to open similar spaces. “In 10 years, I want to have disappeared. I want to be somewhere amongst a few people, not unique.”